Written by Michael Seguin

Boy, this Marie Kondo sure has been in the news a lot lately, hasn't she?

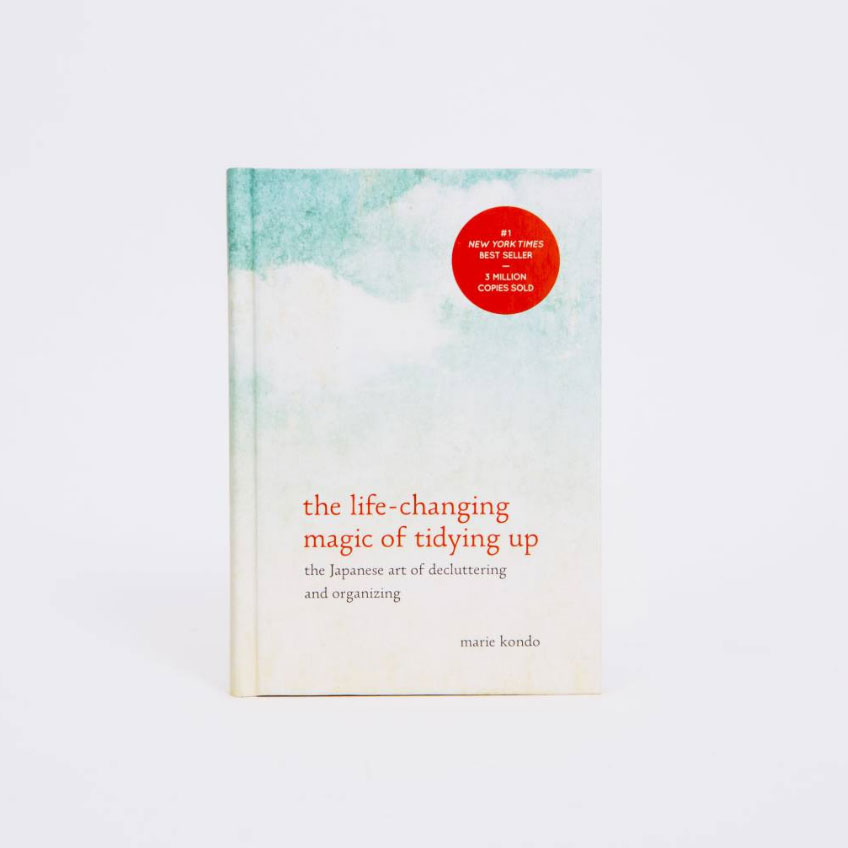

For those not in the know, Marie Kondo is a Japanese organizing consultant who, in 2012, wrote a wildly successful book that reads suspiciously like a manifesto: The Life-Changing Magic of Tidying Up.

The book introduced the now-famed KonMari method, a radical process of discarding and decluttering. The method involves examining every object in one's possession and asking, "Does this item spark joy?" If yes, one should keep it. If not, one should thank it for its service and dispose of it. Rinse and repeat until the entire house is pristine. Oh, and Kondo recommends doing all this in one day, without listening to music.

"Tidying brings visible results," Kondo writes. "Tidying never lies. The ultimate secret of success is this: If you tidy up in one shot, rather than little by little, you can dramatically change your mind-set."

The Life-Changing Magic of Tidying Up espouses the many benefits of a minimalistic, well-ordered homestead, including enhanced clarity and perception. But primarily, the process forces people to consider both what they need and who they are.

"The process of assessing how you feel about the things you own," Kondo writes, "identifying those that have fulfilled their purpose, expressing your gratitude, and bidding them farewell is really about examining your inner self, a rite of passage to a new life."

Kondo has also recently appeared in a Netflix show called Tidying Up with Marie Kondo.

While Kondo's methods have their fair share of detractors, from environmentalists to good old-fashioned slobs, no one can deny that she is a phenomenon.

However, what is most captivating about the KonMari method is not the parallels with ancient Shinto wisdom but those with past writing wisdom.

The idea of decluttering—paring things down and reducing elements to their barest, rawest form—can also be used to teach certain rules for writers.

So, with all this in mind, what can we learn about writing from Marie Kondo?

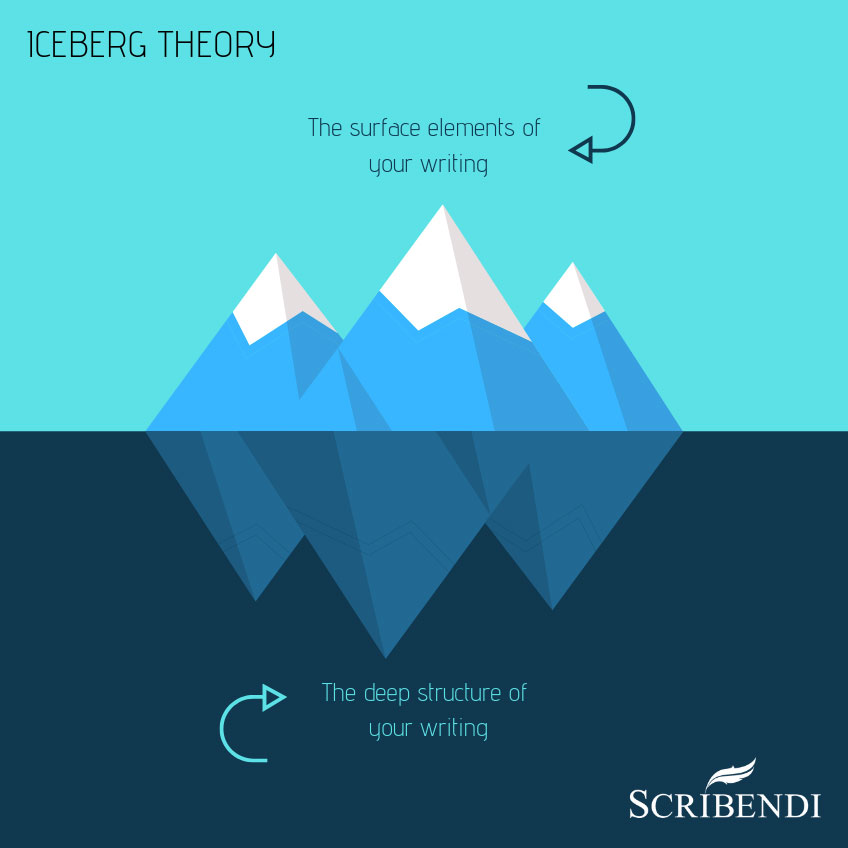

Iceberg Theory

Ernest Hemingway was one of the most influential American authors of the twentieth century, taking home the Pulitzer Prize for Fiction in 1953 and the Nobel Prize for Literature the following year.

However, Hemingway is remembered more for his form than his content. Hemingway's Spartan, taciturn writing style has inspired generations of imitators and duplicators, including J.D. Salinger and Raymond Carver, in large part because of the iceberg theory.

Using his background as a journalist and short story writer, Hemingway focused purely on surface events, such as action and dialogue. This is not to say Hemingway's stories lack depth. Instead, the themes and symbols lurk beneath the surface.

In Hemingway's own words:

"If a writer of prose knows enough of what he is writing about, he may omit things that he knows, and the reader, if the writer is writing truly enough, will have a feeling of those things as strongly as though the writer had stated them. The dignity of movement of an ice-berg is due to only one-eighth of it being above water. A writer who omits things because he does not know them only makes hollow places in his writing."

Basically, while only the tip of the iceberg shows, the true breadth of the narrative remains submerged, waiting to be discovered. (Hemingway also called this approach the "theory of omission.")

Hemingway's resolve to pare down everything but the barest necessities is one Marie Kondo would admire.

How can we apply this as one of the key rules for writers? An old professor once told me that the most boring writers are the ones that tell you everything.

Look at your work and ask yourself these questions:

- What words can be omitted? Can you convey the same idea in one word instead of four?

- Are you repeating yourself? Look for repetition and wordiness.

- Can you simplify the language? Concision is always preferable to arcane verbosity.

Murder Your Darlings

The phrase "murder your darlings" is widely attributed to various authors. Fortunately, none of them were referring to matricide.

In summary, the phrase refers to the draconian attitude one must take when editing one's own writing. You must read your own work as objectively as possible, removing everything that does not forward your argument or narrative.

That's right, everything. The charming little digression about New York City's sewage system on page 11? Bin it. The scene where your character flirts with a waitress for three pages? Hack it. The moment when the main character's mother-in-law reveals she has breast cancer and then never brings it up again? To the cutting room floor.

Tangents. Digressions. Asides. They must all be weeded.

This can be excruciatingly difficult for any writer. And why shouldn't it be? You bled for that melodious prose. Why, it would be a crime to deprive the world of such linguistic beauty. Your heart throbs at the sight of it—hence the phrase "murder your darlings."

Throwing away chunks of your work can be as difficult as throwing away once-cherished belongings. As Kondo writes, this is because our rational brain gets in the way.

"Human judgment can be divided into two broad categories: intuitive and rational. When it comes to selecting what to discard, it is actually our rational judgment that causes trouble. Although intuitively, we know that an object has no attraction for us, our reason raises all kinds of arguments for not discarding it, such as 'I might need it later' or 'It's a waste to get rid of it.' These thoughts spin round and round in our mind, making it impossible to let go."

What is necessary? What is not necessary? What can be removed? Often, much, much more than you think. These rules for writers ask that you look carefully at your writing without being afraid to cut unnecessary elements.

Simplify

A few years ago, Emma Coats, director and storyboard artist for Pixar, shared her 22 tips for storytelling. Numbers 5 and 22 offer a very Kondo-esque view of narrative:

- "5. Simplify. Focus. Combine characters. Hop over detours. You think you're losing valuable stuff, but it sets you free."

- "22. What's the essence of your story? Most economical way of telling it? If know that, you can build out from there."

While no one said it would be easy to simplify this way, remember that nothing you've written is ever truly gone. Discarded scenes and characters have a way of popping up again, be it at a different time or in a different work.

Besides, every moment you spend writing leaves you a stronger writer. It takes thousands upon thousands of discarded pages to master your craft. Most words won't make the entire journey with you.

While it's difficult—sometimes even agonizing—to trim our work this way, according to Marie Kondo, it needn't be a negative experience.

"We should be choosing what we want to keep," Kondo writes, "not what we want to get rid of."

Conclusion

It might be useful to consider Marie Kondo's advice and these rules for writers the next time you're editing a book. But instead of asking yourself, "Does this spark joy?", ask yourself what belongs and what doesn't. Then, thank your words for their service and discard them, when necessary. In the end, you'll be left with a tighter, stronger book. And trust me, a sparser, published book will spark joy in a way that a bloated, unpublished one just can't.

"As for you," Kondo writes, "pour your time and passion into what brings you the most joy, your mission in life. I am convinced that putting your house in order will help you find the mission that speaks to your heart. Life truly begins after you have put your house in order."

Maybe there is something to this Marie Kondo, after all.

Also, have you seen how she folds shirts?

Image source: garloon/EnvatoElements.com

About the Author

Michael Seguin was six years old when he realized that he is going to die. Since then, a peculiar brand of mortality saliency has defined most of his actions. A graduate from the University of Windsor with a degree in English Literature, he operates under the calamitous assumption that he has something useful to say.